Recurse Center: Week 3

Half way

Somehow, inexplicably, I’ve reached the half way point of a six week batch. I keep thinking I’ve made a mistake and recounting where the weeks have gone, but no, here we are.

From logic gates to assembly code

This week was marked by less variety and more focus, as I ploughed at full speeed into Projects 1-6 of Nand 2 Tetris, building up from the logic gates and Arithmetic Logic Unit I mentioned last week, through to assembling the whole CPU and (simple 🙃) computer architecture, to writing machine code, and then (bonus) writing an assembler in Python to translate from symbolic machine code to binary. Compared to wiring up logic gates writing classes and unit tests in Python felt pretty painless, which I’m not sure I could have said a few weeks ago.

The course comes with some handy downloadable tools to help you follow and debug your code as you go. Here is the CPU Emulator running some of the machine code to multiply 2 numbers, one input at RAM address 0 and the other at address 1, and output them at address 2. It takes a little while to get your head around just how many steps it goes through to do this, in particular with all the memory address reassignments, but going through the process from the ground up really starts to unlock the black box.

It was exciting to reach machine code - this is the lowest level I’ve approached before, and only very fleetingly in the Microcorruption challenge exercises last year. And to be honest I bumbled my way through them barely understanding what I was looking at, asking ChatGPT for a lot of help. It turns out things are a lot easier when you take the time to learn them properly! Incidentally another RC attendee Jake Feintzeig worked through these during his batch - he wrote about that and the frankly jaw-dropping amount of other things he took into his stride in his wrap-up blog post last week.

From theory to practice

One of the many cool things about the Recurse Center is its lab of older computers dating from 1977 to 2002. Garrett Bodley was kind enough to give me a tour of the 1980s Apple //e this week, and talk me through their work to compile C code for use on it.

A common way to ’load’ programs to the machine in the 1980s was to connect a cassette player with an audio cable and play recordings that sound like your old dial up modem, of high and low frequencies to convey the program instructions in binary code. And also a 10 second persistent beep at the beginning to start your transmission and make sure your cassette player motor has had time to get up to the right speed (seriously).

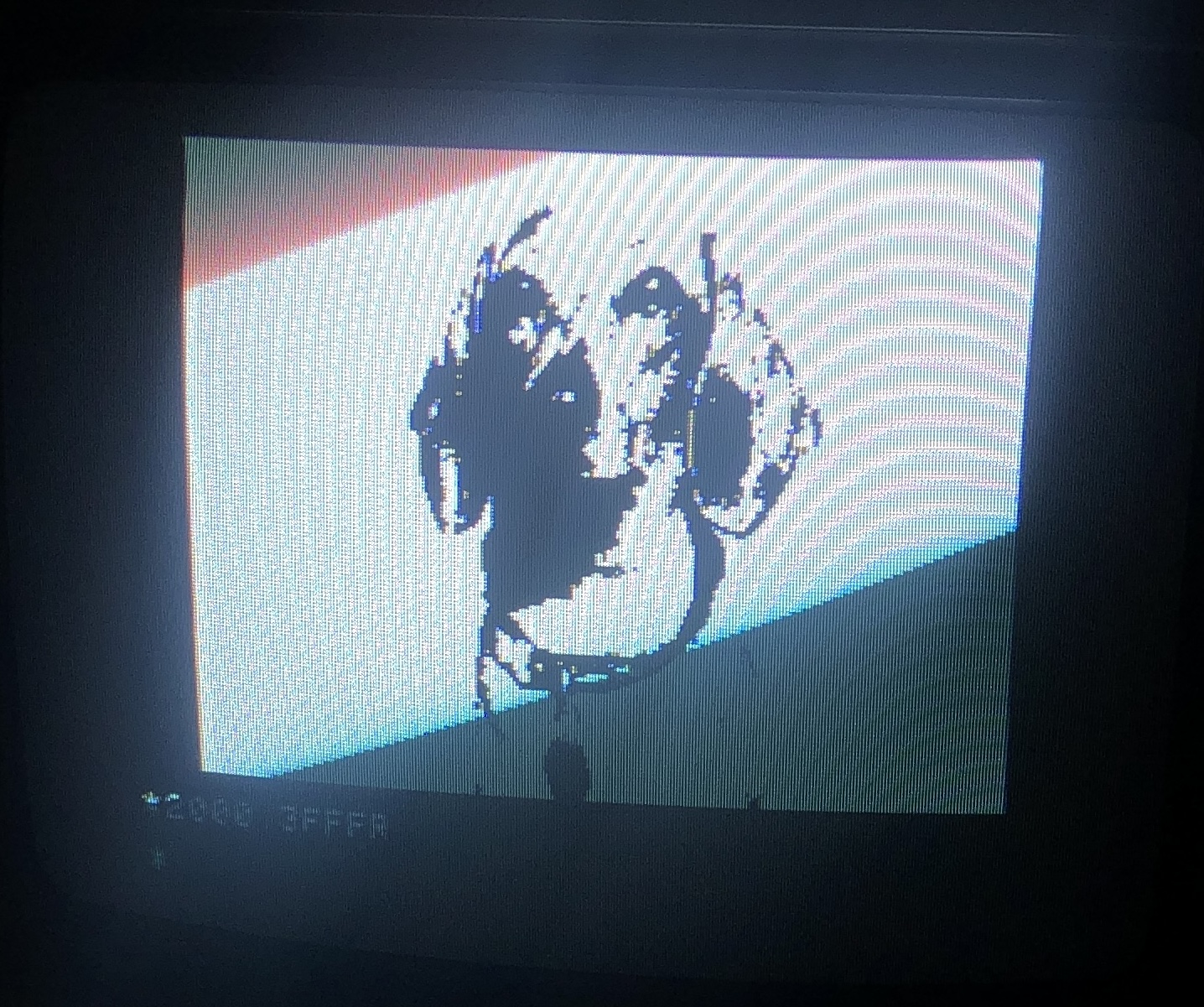

We had fun playing with a project a previous RC attendee has made: a simple site that can translate an image into these audio signals, and get it to paint the picture on its screen. Have a go uploading an image and clicking save to hear those sweet melodious tones unfurl.

Below is 8x sped up - I’d say you could make a cup of tea while the picture paints but then again the kettles are only 120v here and it’s actually kind of mesmerising to watch.

And naturally, Rolo had to have a go too.

Playing around with the machine is a great complement to the Nand 2 Tetris course. Part of project 4 is writing a program in machine language which paints the ‘screen’ black when you press a key on the keyboard, and paints it white again when you stop pressing.

How do you do this? In our little computer the memory at addresses 0x4000 to 0x5FFF (that’s 16384 to 24575 in decimal, or 100000000000000 to 101111111111111 in binary) control what the screen shows. The computer supports a simple black and white display, so a single 1 bit value represents 1 black pixel, and 0 values are white pixels.

Our little computer is 16 bit (i.e. all the instructions it deals with - both memory addresses and machine operations consist of 16 binary digits) and our screen is 512 pixels wide by 256 pixels tall. That means every 32 ‘words’ (chunks of 16 bits) represent one row on the screen. So if you want to put one little black pixel dot in the top right of the screen, you set memory address 0x401F (i.e. decimal 16415, binary 0100000000011111) to a 16 bit binary value of 0000000000000001.

And that’s (basically) how the Apple //e works too! It’s interesting to see how the manual lays out the full specification and architecture of the machine - a far cry from the hermetically sealed devices they sell today.

And this week?

This week I’ll be making a start on the software half of the course I’m following, which will dip into building a virtual machine, writing a simple higher level language, and an operating system.

I’ll also be running a following up session on cryptic crosswords tomorrow after a short intro talk I cobbled together for last week’s non-programming talks. Hopefully the group won’t be reduced to tears by this - I have at least chosen one which doesn’t have any cricket terminology in the clues.