Recurse Center: Week 5

Last week Half way!

This was supposed to be my final week of a ‘half’ batch, but it turns out six weeks is not very long to get stuck into projects, figure out what you want to do, and feel ready to move forwards to the next steps, so a twelve week ‘full’ batch it is.

Rainfall update ☔️

I called time on some of the things I was trying to do with the rainfall animations, but I ran a pipeline on data going back to 1891 (!) and got something basic up here. Big thanks to the people this week who helped me with processing multi dimensional datasets, perceptual colour mapping and the like!

As a reminder, what this shows is a year of cumulative rainfall data (2022).

My grandfather was from Greenock, near Glasgow on the west coast of Scotland. Family lore states that when my grandmother introduced the concept of my grandfather to her mother, a school teacher, her first observation was ‘Highest rainfall in the UK’. Well that makes sense.

Nand 2 Tetris Part 2: Software

Back to the grindstone with this excellent course. Part 2 is all about software, and we start off learning about Virtual Machines. This term can mean multiple things but in this context we are talking about an abstract computer that serves as an intermediate layer between higher level code written in say Java or Python, and the actual base processor hardware and its machine language.

Why bother adding this extra tier to the cake? By defining a language that is not directly coupled to the underlying hardware, it’s easier to write higher level programs that are portable to different architectures. This design was first popularised in the 1970s with Pascal and what were called p-code machines, and regained popularity in the 1990s with languages like Java and C♯. Adding the intermediate pass can also make the code a lot more efficient to run.

It’s not always obvious to an end user (certainly not to me at least) that so much work has to go into configuring systems and making them compatibile all the way down to the fundamental level of the instructions a CPU understands. The reality of modern computers of course is also that there is a lot more going on and no one size fits all approach, but I think it’s still helpful to take away some over-simplified learnings.

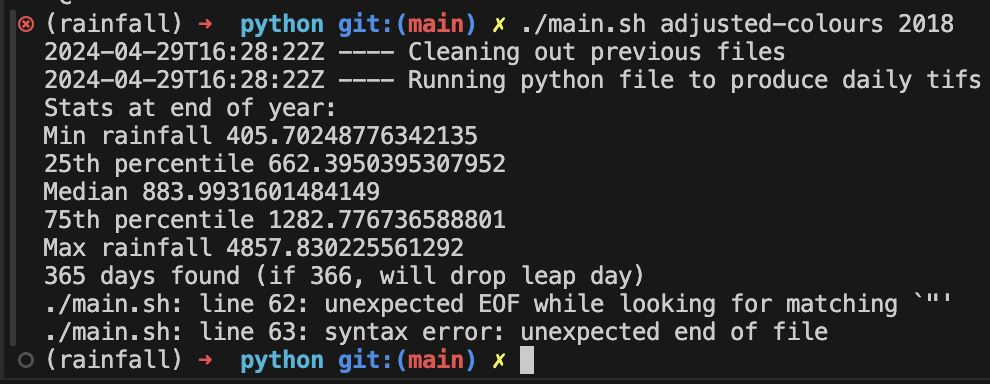

Working on the rainfall project last week I had a little glimpse of some of this in action. The entrypoint to the code I was running to process the images was a bash script which called a few other processes, including a Python file which did the cumulative summing.

The script would take a little while to run for each year because the input files were huge, and sometimes I was tweaking the code as it was running, e.g. adding nicer status logs to different steps. I noticed that sometimes it would error because it was trying to run my incomplete additions to the bash script and this surprised me - I assumed it would only run the file as it was at the moment I kicked the process off.

It turns out no! Rather than going through any pre-compilation steps like Python or Java, Bash is an ‘interpreted’ language. When you run a Bash script its interpreter pulls out just one line at a time to run, ignorant of whatever’s still to come. If you add more lines, it will try and execute them! So if I was adding logs to the Python script I probably wouldn’t see them because all the underlying code to run has been compiled by the time it starts, but not so with the bash steps.

Why is that? I think because Bash scripts are normally used for smaller simpler (more portable?) tasks - usually acting as the glue between running other tools. The work they do wouldn’t normally benefit from adding extra efficiency, unlike the Python scripts. Not needing to compile the code into ‘bytecode’ in advance saves some time when executing the script, even if it may make them slightly slower to run at the moment of execution as they get processed.

One takeway I have from all this is just how big of a task it is to make things work nicely together. It’s one thing to write instructions for a computer, it’s another thing to write instructions that will harmonise with all the instructions written by all the other programmers past and present around you. This gives me some hope for the role of humans in the face of AI and other technological advances. Often the hardest tasks are not the technical ones but the ‘soft skills’ ones - defining goals, coordinating, standardising protocols, motivating free agents to pull together in the same direction. Technology can help with these problems but I think the solutions to them are always fundamentally rooted in people.